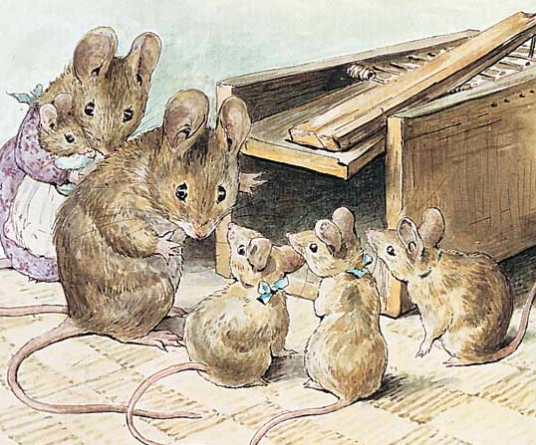

Mouse Nest

At long last, I am an actual, bonafide, legit, published poetess! I am over the moon. My poem, Mouse Nest, is an example of ethnographic poetry. As Cahnmann and Maynard (2010) write,

Poetry is one important place where ethnographers can explore tensions that

emerge between the outside researcher and the community. By demanding

swift associations and evocative language, poetic craft allows the anthropologist

to name and claim subjectivities and contradictions experienced in “the

field.” (p. 7) Full text here.

You can read the brief ethnographic context statement that is appended to the poem as it appears in Anthropology and Humanism, but I am including a bit more backstory below for those who might be interested. To be an anthropologist of childhood in the modern moment is to be unrelentingly vulnerable and on the brink of tears, yet charged with the most fragile of daily hope, that thing with feathers.

Galman, S. C. (2018). Mouse nest. Anthropology and Humanism, 43 (2), 249-250.

I am a preschool ethnographer. On my most recent project, I spent three years and over 1,000 hours as a participant observer in a small, rural New England preschool classroom. In this public multi-age setting I got to know children and their families and community very well, and became a part of classroom life. I set out to explore young children’s pretend play, such as Molly and the narrator in this poem might undertake in the little pretend kitchen, and by doing so sought to understand one location of children’s culture. In the words of James, Jenks and Prout (1998) this was also a project aimed at affirming rural children’s agency and intentionality to continue to “provide the tribes of childhood … with the status of social worlds’ ensuring that such a form of child life can begin to receive detailed annotation” (29–30). About halfway through my time in preschool there was a shooting at another elementary school, just a short drive away. A group of 1st graders were murdered, and my research site was palpably altered. Bulletproof glass was installed, along with flashing lights. We began doing “lockdown drills” of a heightened sort. I watched as the children picked up on changes in the teacher’s voice, changes in practice (we used to just sit in a circle on the carpet, but now we turned out the lights and huddled in the bathroom and had to be completely silent) and changes in urgency. As Graue and Walsh (1998), Henward (2015) and other preschool ethnographers will attest, children’s culture is so much richer and more nuanced than a mere function of adult culture, but it does keenly take the temperature of adult joy, anger, sadness and fear. The children (and, to be honest, the adults as well) believed that danger was near that day, but as the narrator describes, they were unable to put to words what form it might take. My ethnographic involvement at this site is over, but the lockdown drills continue. As they do everywhere. I have requested that my own children no longer participate in lockdown or “active shooter” drills or similar and I strongly suggest that you do the same. Until the government can protect children in school in meaningful ways no child should be made to rehearse for death like fish in a barrel. No more upping the ante. Draw the line today.

James, A., C. Jenks, and A. Prout. 1998. Theorizing Childhood. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Graue, M. E., and D. J. Walsh. 1998. Studying Children in Context: Theories, Methods and Ethics. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Henward A. S. 2015. “She don’t know I got it. You ain’t gonna tell her, are you?” Popular culture as resistance in American preschools. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 46(3): 208–223.